A commentary on How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan (Random House, 2018)

and

The Netflix Mini-Series of the same title (July 2022)

and

The Immortality Key by Brian Muraresku (St. Martin’s Press, 2020)

Having only belatedly viewed the 2022 NetFlix series a few weeks ago, I see that I have missed some interesting developments concerning a topic I have myself explored in "Mixing the Kykeon",1 and "Bread of Heaven or Wines of Light: Entheogenic Legacies and Esoteric Cosmologies"2 and The Road to Eleusis - Thirtieth Anniversary Edition. (uncredited on the cover, but the title page lists me as having contributed the Appendix

Nor had I paid much attention to the Joe Rogan sessions with Pollan or Muraresku since the Spotify internet platform is received quite badly here. But I had already sped-read Pollan's book, like I usually do for books on a subject I have been a little more than merely acquainted with. The method is to browse the Table of Contents, then the Index, and then check out the various sections where something new (for me) might appear. Pollan's index is extensive, so I had expected to read quite a few passages on referenced subjects.

First up, I looked for Eleusis, then ergot. Nothing! Greece. Where's that? Well, I guessed Pollan was primarily interested in the modern rediscovery of psychedelics and their uses, and especially to relate the story of his own journey to psychedelic awareness. Yet the Bibliography does list The Road to Eleusis. And then, I discovered that a search of the e-book version does turn up a brief mention of all these terms, and that the index of the e-book is more complete than the paperback version in my possession.

Still, the brief mentions of Eleusis and ergot are just that: brief, with no indication of the significant and continuing scientific debate about the Eleusinian Mysteries and the makeup of the notorious potion that was used to transport large gatherings of pilgrims to states of transcendence and spiritual awakening. This cannot be because of a lack of relevant source material from which to analyze and quote. The subject and debate, of course, goes back nearly 50 years to the first publication of The Road to Eleusis. But, How to Change your Mind is already quite long, and perhaps Pollan ignored a topic or two for brevity.

Wherever else I was guided to by index entries, however, a wealth of information was available, often newly illuminating some topics I already thought I knew about. An example: a rather surprising revelation on R.G. Wasson's trip to Mexico and the psilocybin mushroom session with Maria Sabena. Or the entertaining story of a psychedelic mushroom hunt with Paul Stamets. No need to elaborate further, Pollan's book is excellent, entertaining, and I almost wish I had little or no knowledge of psychedelics so that I could remedy my ignorance by enjoying a thorough reading! On to the NetFlix series, then.

A big surprise was in store watching part 4 of the Netflix series. I noticed a major addition to episode 4 that was nowhere covered in the book. When I say "major" addition, it is not because of the length devoted to the topic, it is only 1 minute and 9 seconds long! It is the special importance of the topic itself: the probability that the ancient Greek celebration at Eleusis involved a psychedelic preparation, the kykeon, and that it was derived from the parasitic fungus, ergot (Claviceps purpurea). The film presents a short view of the Eleusis location as it is today, and then a "vessel" is shown, a small cup of some sort, that supposedly contained traces of beer and ergot. This very short scene was seemingly tacked on near the end of the episode that dealt with Peyote, almost as an afterthought. The importance of the subject would have merited even a part 5 for the mini-series in my view!

How did that get inserted into the series? And why — somewhat incongruously — in the episode devoted to peyote? And where was the "church" pictured in the film clip? It doesn't appear to be at Eleusis. And above all, what was the origin of the "vessel" pictured? It had no resemblance to any of the items of pottery that I had seen in articles and papers about Eleusis. And why, at the opening of this brief segment, are we shown a rather blurry and low quality vista of the modern-day Eleusis site? In other parts of this documentary, high-quality images were shown for many other locations, why not for Eleusis? It could seem like the segment was indeed hastily added on at the last minute due to the influence of...

I believe the short answer to all these questions is: Brian C. Muraresku. Or to be more specific, BCM and various backers, promoters, journalists, producers, investors, psychedelic-science insiders and other assorted interested parties. More on this at the end of the article.

A little internet research turned up the following:

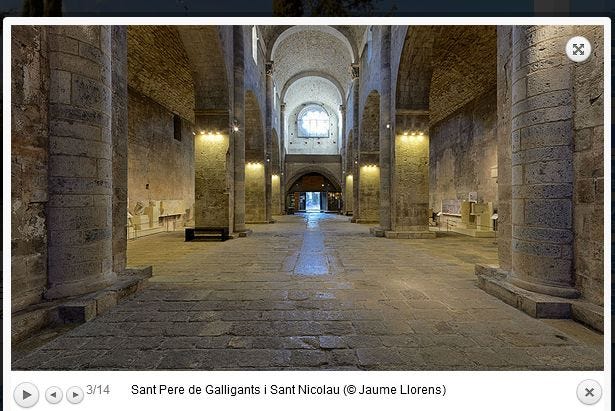

The vessel pictured in the film, [image] does not come from Eleusis, Greece, as one would justifiably believe from watching the film, but from Spain.

And the "church" on the floor of which is shown the vessel, is not in Eleusis, but Girona, Spain. It is a 12th century Benedictine monastary, Sant Pere de Galligants.

In BCM's The Immortality Key, as well as several podcasts, invited talks, etc., we are treated to the story of how he invited Carl Ruck to visit the Archaeological Museum in Girona to view the vessel that, according to the 1997 analyses by Jordi Juan-Tresserras, was claimed to contain traces of ergotized beer. In my view, BCM was in the book and in at least one invited talk, quite disrespectful of Carl, calling him a "nutty old professor" or making him the butt of a joke. Young whippersnapper derides his betters! So there.

And perhaps rather oddly, another development: in 2023, long after the book had attained New York Times Bestseller status, and even longer since the unearthing and testing of the vessel (1997), three separate Spanish periodicals suddenly decided to publish articles about the 26-year-old discovery of the "holy grail" of Eleusis, the kykeon.

A la búsqueda de una poción alucinógena de la antigua Grecia en Pontós - El Periódico

Busquen nous vestigis d'una poció inèdita del segle III a.C a Mas Castellar de Pontós

El secreto de la bebida psicodélica de la Grecia Antigua podría encontrarse en Cataluña

Reviews

Concerning The Immortality Key, I need not provide a detailed review here since very appreciative reviews are readily available, and tell the story well enough. The number of very positive blurbs from notable experts at the beginning pages of the book are almost unprecedented, almost suspicious for an author's first book. Also, I do not have the necessary expertise on the 3000+ years of history and all the ancient writings BCM discusses, to make any meaningful critique on that account. But here are two reviews that do the job well:

Graham Hancock, ed., Two Reviews of The Immortality Key, May 2021

Review 1 by Jerry B. Brown, originally in Journal of Psychedelic Studies, March 2021

Review 2 by Chris Bennett, "The Immortality Key: Lost on The Road to Eleusis"

Both are required reading for those interested in these books and the Eleusis debate. The review by Chris Bennett, "Lost on the Road to Eleusis" is excellent and thorough, and exposes in great detail where the book succeeds, and where it fails. Like Chris, my own views here are "in no way intended to dissuade the interested reader away from The Immortality Key", and a reading of the book certainly impresses one with BCM's research and knowledge of his subject matter.

Nevertheless, as in Chris' review and title, BCM certainly gets lost along the Road, but my own expertise will show where he lost it concerning the chemistry and botany of ergot. And this, I claim, is the most serious challenge to BCM's overall treatise. If he hasn't got the chemistry and botany of ergot right, all the rest is poised on a very shaky foundation.

Eleusis Mystery Solved

In 2001 I published my solution of the mystery in the journal ELEUSIS, with accompanying commentary and analysis by Daniel Perrine and Carl Ruck. The paper is freely accessible at Academia and at my Website/Library, so I won't bother to summarize or quote passages from it here. But this too is required reading for those interested in the Eleusis debate.

The article was well received, with the editor of the journal, Giorgio Samorini, writing me that, "Enjoy Eleusis 4, and thank you for your important contribution. Your article will become an "historical" article, or at least, this is my impression... Indeed it is really a good article, and I'm thinking now you may really have found THE KEY concerning the Eleusinian Mysteries. My full compliments for this." [personal email communication]

In 2006 I presented a lecture on the matter to an enthusiastic audience attending the greatest psychedelic conference ever held, the 100th Birthday Celebration for Albert Hofmann at the Basel Conference Center in Switzerland. Here too, my theory was well received, but a discordant note or two crept into the scene, with a famous psychedelic chemist telling me to my face that if my audience had been professional chemists I would have been "laughed off the stage". I let that roll off like water off a duck's back since the little conversation had started with he in a very bad mood, complaining about how he had to pay his own way to the conference. A little later I realized he had probably been at odds with my extension of the theory, claiming that the equilibrium mixture of ergine and isoergine was the actual psychedelic agent. The mixture is naturally produced by the partial hydrolysis process.

Solution Forgotten

It was at least a small surprise then that Michael Pollan had nothing substantial to say about Eleusis in his book, but then a bigger surprise that a segment of the NetFlix docmentary showed a pot that had been recuperated at a dig — not at Eleusis — but in Spain! The narrative said that an archaeologist from the University of Barcelona had discovered "traces" of the famed drink in the small vessel pictured in the documentary.

This brought back memories of discussions I had had with Carl Ruck in 2001 about the possibility of obtaining some "traces" of the kykeon drink from vessels that had been unearthed at Eleusis, and further discussions with Vladimir Kren

about exactly which chemical markers might indicate that ergot fungi had been employed in the preparation of the kykeon. This is not at all a simple matter — one cannot simply say that one has discovered some "traces of ergot" in a vessel as the Spanish reports did, without showing exactly what decomposition products had been shown to be present, and why those products would allow the claim that they had been derived from ergot.

Furthermore, and I would welcome some insight on the matter, "optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy" don't seem methods that could identify specific molecular entities such as ergot alkaloids and/or their decomposition products. Such techniques may well be able to detect small fragments of barley or ergot sclerotia, but as we shall see presently, the road to a kykeon is not at all indicated on those maps! After all, when perishable organic compounds are subjected to great periods of time in the ground, and who knows what stresses from weather conditions, groundwater contamination et al., it is no easy task to devine what might have been produced during the inevitble decompositions.

BCM, apparently having ignored my two papers, likewise ignores many facts about ergot as a fungus, and ergot as a source for alkaloids that in the raw are poisonoius, and without a conversion process as described in "Mixing the Kykeon", are neither safe nor effective as psychedelics.

BCM seems to come to rest on the proposal that the kykeon was an ergot-laced beer.

Beer is made using whole grains of a cereal, such as barley. All throughout history, barley and other cereal grains were always contaminated with ergot since the fungus must grow and infest its hosts every year. Ergots cannot fall to the ground, and remain fertile there for a couple of years or more as do many seeds of flowering plants, so if the ergot species is to survive at a particular place, the ergots must sprout and contaminate their host cereal grain the following spring.3

Therefore, all grain used for making beer would have had at least a trace of ergot included. Ergot was everywhere in lesser or greater quantities. It would not be surprising therefore if testing of all sorts of vessels associated with foodstuffs revealed traces of both barley and ergot, but that is not at all reason to conclude the vessel contained a psychedelic potion!

There are further problems for analysis of vessel traces and concluding that the vessel was used for the kykeon. An ergot-laced beer would not be psychedelic unless the beer-making process, similarly to the method described in "Mixing the Kykeon", was efficient at converting the toxic alkaloids to ergine/isoergine. Otherwise, one would have a non-psychedelic beer that contained harmless traces of ergot (ergot in small amounts or low potency ergot), or more seriously, doses that could lead to vasoconstriction and the beginnings of ergotism (large quantities of ergot produced in years of favorable weather, see below).

And I believe I am corect in saying that all through the beer-making process, the pH of the mixture, and final product, is acidic, between perhaps pH4 and 5. Thus the partial hydrolysis process described in "Mixing the Kykeon", which requires high pH, could not have occurred, and ergotized beer, no matter what the source or quantity of ergot, would contain only the unconverted toxic ergopeptine alkaloids.

A further problem arises when we consider that in either proess, the ergotized beer-making of BCM, or the partial hydrolysis of "Mixing the Kykeon", a sufficietly large batch of the product would need to be prepared in advance, in one or more quite large vessels. One could not brew ergotized beer, or the potion of "Mixing the Kykeon", in the tiny vessel shown by BCM. This vessel, if actually used to distribute the potion, would have been a single-dose vessel, and so should not contain any ergot sclerotia fragments itself. For ergotized beer produced in a large vat or other container, the processed product would have been filtered or decanted into another large vessel from which the libation was poured into individual singe-dose cups such as the one pictured. The contents, and thus any traces that remained in the pores of this vessel, would be only the final active ingredients, i.e., lysergic acid alkaloids, not fragments or other markers of the ergot fungus itself.

Consider bread-making. We have the same problem: cereal grains have been constantly parasitized with ergot since the first stages of the agricultural revolution. And plagues of ergotism have resulted in the mostly infrequent years where ideal weather conditions allowed the ergot to produce high levels of alkaloids. This is the reason why ergotism was such a sporadic disease despite there being minor or greater amounts of ergot sclerotia in most if not all harvests. In most years, the natural ergot content of cereal grains would be harmless. Neither ergotism-producing nor psychoactive if made into beer or bread. If naturally ergotized beer is supposed to have been psychedelic, then naturally ergotized bread should also have been psychedelic, and that is certainly not the case. Both beer and bread making involve heating, but an absence of a highly basic — high pH — ingredient that could have actuated the partial hydrolysis necessary to convert the toxic ergopeptine alkaoids to the simpler, psychoactive alkaloids ergine and isoergine.

A further complication is that the appearance of ergot on its host has all through history led to the conclusion that ergot was merely malformed or sun-burned, deformed or “rusted” grains of the cereal host in question. It wasn’t until the late 19th Century that ergot was generally recognized as another species altogether, a fungal parasite of the grain on which it appeared. Thus the Greeks very probably also made this error. And all ancient "recipes", medical or otherwise, that list barley as an ingredient, should be understood on those terms.

Are You Experienced? (Jimi Hendrix)

Muraresku admits no direct experience with psychedelics. Forgive me if this observation might be considered insulting, but to write a book that claims expertise on the psychedelic experience without at least entry-level sessions with the substances would be the equivalent of writing a travelogue on the Grand Canyon without ever having visited the place. The purported objectivity of the psychedelic-inexperienced scientist is praised in some circles, but a knowledge of the actual territory seems to this writer a certain advantage, hardly a disqualification.

So for BCM one psychotropic is as good as another. He mentions all sorts of psychoactive plants that have been used since time immemorial — henbane, belladonna, opium, mandrake, cannabis etc., as if these products too might have been included in beer or wine recipes, and acted as psychedelics. With personal experience of a true psychedelic such as the three majors, one would know beyond a shadow of a doubt that these hallucinogens, soporifics, downers and coma-producers are certainly not candidates for making a potion capable of producing spiritual ecstasy and illumination in a large gathering of pilgrims such as at Eleusis.

True, I mention in my paper Psychedelic Elephant that shamans could and can use various psychoactives, even tobacco, in one-on-one situations, and activate and amplify salience detection in their patient and indeed, themselves. Any significant alteration of consciousness, even through meditation, fasting, extreme sport, etc., and especially with the participation of a guide or elder providing the appropriate set and setting, can result in a measure of psychedelic experience. The question for Eleusis is whether any psychoactive other than ergine/isoergine could suffice without producing highly undesirable effects on most of the congregation. Cannabis parties for newbies are mostly giggle-fests. Beer at an English pub seldom produces collective spiritual awakening. Witch's ointments produce semi-coma during which dreams of flying to devilish locations is the norm. Opium... we all know what that produces.

In order to complete the arguments made in "Mixing the Kykeon", rather than re-compose a version for this paper, I append here an edited version of my January 2005 part 2 of "Bread of Heaven or Wines of Light: Entheogenic Legacies and Esoteric Cosmologies". This should bring a clear understanding of the chemical considerations in the Eleusis debate:

It was over twenty years ago that I first came across the lines of Rumi’s Masnavi I Ma'navi reproduced at the beginning of the preceding essay by Frederick Dannaway and Alan Piper.

Alas! the forbidden fruits were eaten,

And thereby the warm life of reason congealed.

A grain of wheat eclipsed the sun of Adam,

as the Dragon's tail dulls the brightness of the moon.— Rumi: Masnavi I Ma'navi

Immediately upon reading them it seemed a good guess that the medieval Sufi poet’s reference to wheat as the forbidden fruit betrayed a still-lingering knowledge of one of the oldest and longest-enduring religious rites ever practised, the yearly autumnal celebrations at Eleusis in ancient Greece. At that time, The Road to Eleusis (Wasson, Hofmann & Ruck 1978) had just recently been published, describing in detail a new theory about the Eleusinian Mysteries, and suggesting ergot as the long-secret component of the psychoactive beverage of the Celebrations, the kykeon. For a long time, however, I was unable to follow up my suspicion with further evidence, and even when in the early 1990s I decorated the homepage of The Psychedelic Library [http://www.psychedelic-library.org/] with Rumi’s lines next to a head of grain infested with ergot (Claviceps purpurea), it attracted no comment or confirmation.

Only in the past year have I finally met Frederick Dannaway and Alan Piper thanks to the ever-widening “friend of a friend” web of Internet communications — and found that references to wheat as the forbidden fruit are not at all rare. Quite the contrary. As we may infer from the previous essay such references may constitute further significant evidence supporting the Wasson, Hofmann & Ruck hypothesis, that the enlightening beverage consumed at the Eleusis Celebration was a psychoactive preparation made from ergotised grain.

The suggestion that ergot may have been a psychoactive constituent of a sacramental beverage or preparation has understandably been met with criticism, even total disbelief. A major problem, of course, is that this common parasite of food grains such as barley, rye, and wheat is toxic, sometimes extremely so in years when high alkaloid production is favoured by ideal weather conditions. The history of medieval plagues of ergotism are seen as evidence that C. purpurea could hardly have been used as an otherwise benign psychoactive agent.

Since the publication of The Road to Eleusis over a quarter-century ago, scholarly opinion on the matter has divided itself into three camps:

those who dismiss outright the idea that consciousness-altering drugs have been part and parcel of humankind’s religious and social evolution since earliest times;

those who admit the evidence of such a scenario but believe ergot could not have been suitably psychoactive and at the same time safe;

and those of a third group who have tried to extend and improve upon the original suggestions of Wasson, Hofmann, and Ruck.

The first group of scholars — classicists, anthropologists, chemists, religious leaders and scholars, professors of various disciplines, et al. — although they are apparently a large majority of those who claim some expertise on such matters, may be dismissed completely as being sadly and wilfully ignorant of the great body of evidence showing the essential and necessary connection of consciousness-altering plants and the entire history and prehistory of the human race. Whether these scholars have fallen under the spell of that great 20th century crowd madness and destroyer of clear thinking, Prohibitionism and support for the “War on Drugs,” is an interesting hypothesis to be tested. But we can be certain that seeing “drugs” as the “scourge of humanity” has led to no small number of experts demonstrating a monumental narrow-mindedness concerning other scholars’ work on the subject.

The fact of the matter is: the seeking of ASCs (altered states of consciousness) is a human universal as defined by the anthropologist Donald E. Brown [Brown 1991]. And far from being a perversion or abnormal activity as today’s prohibitionist mentality would have it, using plant-derived substances in the pursuit of altered consciousness is a biologically natural and normal behaviour, and very likely has adaptive evolutionary value [Weil 1972, Siegel 1989]. Such a universal and powerful drive is not even humanity’s own, for it has most persuasively been shown by Giorgio Samorini that seeking out and ingesting consciousness-altering drugs is a pursuit that appears across the entire animal kingdom, and thus we humans are the mere inheritors of this instinctive primary motivational force. [Samorini 2000] So much for those who pine for a “drug-free” society, science, history, evolution, and religion.

The second group — those who are well aware of the importance of psychoactive drugs throughout history and prehistory but who question ergot’s possible role and use — have suggested various other candidates for the Eleusis sacrament, the kykeon. I have countered their criticisms of the ergot hypothesis, and their suggestions for alternative psychoactive agents elsewhere [Webster, Perrine & Ruck 2000], and need not repeat those arguments here. What concerns me here is to restate and elaborate on certain observations I made in the above cited article, particularly in reference to more recently-presented ideas about other possible ways ergot might have been prepared for sacramental purposes. [Reidlinger 2002, Pyle ca. 2001] And in light of the accumulating evidence for the ergot hypothesis of which part 1 of this paper is an important new development, my objective is to attempt to bring some consensus among our group of researchers — the third above-mentioned camp — concerning the most likely and most parsimonious hypotheses for producing a suitably psychoactive preparation from ergot. If the means to conduct some experimentation on these questions arise, hypotheses such as these should of course be the first to be tested. As it will be seen, these hypotheses are also very easy to test, more so than those of Reidlinger and Pyle.

Albert Hofmann had originally suggested in The Road to Eleusis that a simple water-extraction of C. purpurea might have accomplished a separation of the toxic alkaloids of the fungus (the ergopeptines) from the much smaller fraction of a simpler, water-soluble lysergic acid amide, ergonovine, which does apparently have some psychoactive activity, albeit somewhat disputed. Such a process, it was noted, would eliminate the toxicity of whole ergot.

In a more complex hypothesis, Reidlinger proposes that the kykeon might have been produced via a “double-decoction” process similar to a recently discovered beer-making technique used in ancient Egypt. I need not criticise Reidlinger’s very imaginative and well-researched ideas — they certainly are worth pursuing experimentally if the opportunity arises — except to say that they have one major problem: the result of the process would still leave ergonovine as the essential psychoactive agent in the preparation. As Reidlinger himself notes, the self-tests by Hofmann with ergonovine leave considerable doubt as to its possible candidacy as an entheogen of sufficient and suitable effect to have resulted in a 2000-year history of highly successful use. Reidlinger is right on-track, however, in his observation that the toxic alkaloids of ergot — the ergopeptines of which ergotamine usually predominates — are the primary problem: they can cause ergotism, spontaneous abortion, and are not at all suitably psychoactive. Somehow they must have been excluded from the kykeon.

Another problem for the hypothesis that ergonovine was the psychoactive agent of the kykeon is that it is only a minor and quite variable constituent in the alkaloid mixture produced by C. purpurea, with alkaloid production itself quite variable according to weather conditions. C. purpurea production on barley (as opposed to rye) also appears to favour the ergopeptine (toxic) alkaloids with ergonovine being even less present. [Kren & Cvak 1999] Thus simple water-extraction of ergot, or Reidlinger’s double decoction process, would both have been — year-to-year — processes very unlikely to be reliable and reproducible, certainly not something that worked without a fault for 2000 years in a row.

I would add just one further note on Reidlinger’s paper. He certainly over-estimates the toxicity of ergot and ergotamine when he suggests that the lack of trials with ergot according to these extraction recipes might be because of the fear of toxic effects by potential experimenters. Ergotamine is widely used for various medical conditions — I myself use it for migraine — and it is well-established how much ergotamine one may take without risk, and how frequently. Also, it is well-established how much ergotamine may be contained in a sclerotia of ergot — also highly variable according to weather conditions — so knowing these details would easily enable one to prepare a trial kykeon from assayed ergot and sample it without risk, even if one did nothing to remove or otherwise neutralise the toxic components.

More likely, in my opinion, those who might have tested a procedure for making a kykeon simply did not have a hypothesis convincing enough to them to merit carrying out a trial.

Another hypothesis as to how ergot might have been used has been proposed by Pyle, who suggests that ergot may have been fermented in solution to produce lysergic acid alkaloids. Indeed, with the increasing pharmaceutical demand for these products in the 20th century, fermentation processes were developed to produce lysergic acid and several of its amides in saprophytic culture — the ergot mycelium being grown in nutrient-rich solutions to produce alkaloids without the sclerotia or fruiting bodies of ergot ever appearing. But these processes are highly technical, and the alkaloids produced are highly dependent on the isolation of certain sometimes rare strains of the fungus, requirements beyond the capabilities of the ancient Greeks to be sure. It may be possible to effect some fermentation of C. purpurea in a simple barley broth, but even if alkaloids were produced, they would still be primarily the toxic ergopeptines, with ergonovine as a possible minor product and the only candidate for psychoactivity. So we arrive back at the same problems we have as above.

Our own hypothesis for an ergot recipe, described in “Mixing the Kykeon”, overcomes all these problems. Unlike suggestions for alternative psychoactives such as Psilocybe or opium made by some, it remains true to much of the evidence first presented in The Road to Eleusis, it overcomes the problem of toxicity of the ergopeptine alkaloids, and it does not depend on the disputed psychoactivity of ergonovine. The only way to make the alkaloids of ergot safe and psychoactive at the same time, and also to employ the major fraction of alkaloids — the otherwise toxic ergopeptines — is to process the ergot in a way that leads to the conversion of the ergopeptines to the simple amides ergine and isoergine. These two amides, mirror-images (epimers) of each other and always in approximate 50/50 equilibrium in solution, are the principal component of the ancient Central American entheogen ololiuqui, whose psychoactive properties cannot be in doubt.[Jonathan Ott in email] References showing the fact of this conversion and under what conditions it occurs, and discussion of the distinct possibility that the ancient Greeks may well have discovered it — the partial hydrolysis of ergopeptine alkaloids — may be found in our paper, “Mixing the Kykeon”.

I mentioned above that this hypothesis is the easiest to test. It would suffice for preliminary results to digest powdered pre-assayed ergot with wood ash and water, as described in our essay “Mixing the Kykeon”. Trials would use various concentrations of ash, at various temperatures and for various lengths of time, and analyze the alkaloid spectrum and its changes using thin-layer and/or other chromatographic techniques. [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2016.00015/full] This would be very easy and economical to do. Forensic laboratories everywhere know of these techniques since they are routinely used in prosecutions of illegal possession and manufacture of LSD or other "hallucinogens". This may well be a reason why no chemist we have contacted has followed through on such testing: a fear that some "authority" might see such a proof and publication as providing an easy way to make stupéfiants (the French derogatory term for all illegal drugs).

To continue with the necessary: Once the optimum conditions had been established where the maximum conversion of the ergopeptines to ergine/isoergine was achieved, a trial kykeon could be prepared and tested without risk.

NOTE: for enthusiasts of BCM's ergotized beer hypothesis, and/or others who have tried to cast doubt on the Mixing the kykeon hypothesis for lack of trials and perfection of the method, the same onus applies. Show us all a plausible recipe for making ergotized beer and show how it excludes the toxic ergot alkaloids while somehow being psychedelic.

Given its New York Times best-selling status despite BCM being little known beforehand, given the wide praise of the book such as at BCM's website — all this despite the JB and CB critical reviews — and even the late appearance of the Spanish magazine articles, one might wonder how all that happened. As for the two critical reviews mentioned, according to Graham Hancock's website,

I expected The Immortality Key to be controversial, and to attract censure from orthodox historians of religion. I assumed that reactions from other researchers more closely aligned with Brian’s distinctly unorthodox take on things would be universally positive and supportive. I was therefore surprised by the positions taken by Chris Bennett and Jerry Brown, both well-known figures in the field of psychedelic studies. Their reviews of The Immortality Key had already been published elsewhere but I felt that their perspectives were worthy of wider discussion and would be of interest to my audience (since, after all, I had contributed the Foreword to The Immortality Key and thus had my name on its cover alongside Brian’s). I therefore suggested we republish them on my website together with a rejoinder from Brian Muraresku.

Unfortunately, Brian tells me he is at present exhausted from overwork and unable to respond. I therefore publish below only the reviews from Chris and Jerry without the hoped for rejoinder from Brian. Possibilities are being discussed for a live debate, online, perhaps in September. I will post an update here as soon as I have definite commitments from all parties.

—Graham Hancock, 20 May 2021

Nothing so far... I did note that despite BCM's "exhaustion" he did subsequently appear on several podcasts, talk-shows, invited lectures... On one of them the host said at the end, "we are not allowed to take questions from the audience."

Am I being unkind?

Is there a (ha-ha) conspiracy to seize the narrative about Eleusis et al.? The events (coincidences of course!) described above emanate an unmistakable whiff of big money. As Pollan mentions in a JULY 2022 review of the NetFlix series in TIME magazine:

I’m a little less excited about the gold rush as capital floods into the space. There are now, at last count, 350 [psychedelic-related] companies. It seems to me there is more capital than there are good ideas—and there are some really bad ideas. There are attempts to grab territory, with the patent law. There’s psychedelic tourism; lots of retreat centers are getting established in the Caribbean and Central America. Capitalism is doing its thing with psychedelics, and that we’ll have to see how that shakes out.

And even Pollan's book enjoyed unexpected meteoric success, to Pollan's surprise:

From what I hear from other people, it has had a tremendous impact—and one that, to me, is completely surprising. This was kind of a fringe subject in 2018, when the book was published. There was not a lot of attention being given to psychedelics; there were a handful of trials underway. And in the years since, we’ve seen an explosion in the amount of research, the number of companies, and the amount of press coverage. The other day, I met somebody who was involved with a trial at UCSF for a coffee, and she said, “Do you realize that in the research community, we talk about ‘pre-Pollan’ and ‘post-Pollan?'” “Pre-Pollan” was a time when it was very hard to get funding, very hard to get approvals, very hard to get taken seriously. And now that’s all changed. It’s legitimate research; there’s no stigma attached to it.

BigMoney, BigPharma and DeepState influence to capture the narrative of the psychedelic scene, take it away and scrub it clean from its long-time experts and enthusiasts, some still hanging on since the sixties, the "nutty old professors" and some other less public figures among whom have been outlaws, or those without university or foundation affiliation, or who have not even graduated university, not members of the current psychedelic in-crowd? A concerted BigMoney BigPharma effort to make the whole shebang into a new medical boon with gigantic profit possibilities? Absurd accusation for some, no doubt. But what BigMoney, BigPharma and DeepState did to promote the COVID debacle, a Biblical-Strength Abomination in this writer's view

surely illustrates what this DeadlyTrio are capable of when they get in the mood and Big Bucks Beckon.

References for Bread of Heaven or Wines of Light

Brown, Donald E. Human Universals. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Kren, Vladimír & Cvak, Ladislav. Ergot. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1999.

Pyle, Tim. Personal communications in 2001-2002.

Reidlinger, Thomas J. “Polydamna’s Drug: Egyptian Beer and the Kykeon of Eleusis”, in Entheogen Review IX, 2, 2002.

Samorini, Giorgio. Animals and Psychedelics: The Natural World and the Instinct to Alter Consciousness. Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press 2000.

Siegel, Ronald K. Intoxication. New York: E.P. Dutton 1989.

Webster, Peter; Perrine, Daniel M.; Ruck, Carl A.P. “Mixing the Kykeon”, in ELEUSIS: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds, New Series 4, 2000.

Wasson, R. Gordon; Hofmann, Albert; Ruck, Carl A.P. The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1978 Republished in a Twentieth Anniversary Edition with additional material.

Weil, Andrew. The Natural Mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Comapany 1972.

Webster, Perrine and Ruck - ELEUSIS: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds New Series 4, 2000

Dannaway, Piper, and Webster - Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Dec 2006